The Tenth at the Time of the World Wars

At the outset of World War 1, many of the Tenth’s old boys enlisted in the 14th Battalion Royal Irish Rifles (Young Citizen Volunteers). The YCV movement had been started in Belfast in September 1912, to encourage good citizenship along the lines of the Scouts and the Boys’ Brigade but for an older age group. A large number of the young businessmen in its ranks were later commissioned in the British Army. Ostensibly non-sectarian and non-political, the organisation was drawn by the Home Rule crisis into the arms of the Ulster Volunteer Force. Thus, when war with Germany (rather than civil war) broke out, Young Citizen Volunteers became soldiers of the 36th (Ulster) Division. They gained the nickname of ‘Young Chocolate Soldiers’ because of their comfortable, middle class backgrounds. But there was nothing soft about the training at Shane’s Castle and at Finner in County Donegal, as they learned to use the rifle and bayonet, dig trenches, and sleep in the open. Nothing could have prepared them for the Battle of the Somme, though, which erupted on 1 July 1916.

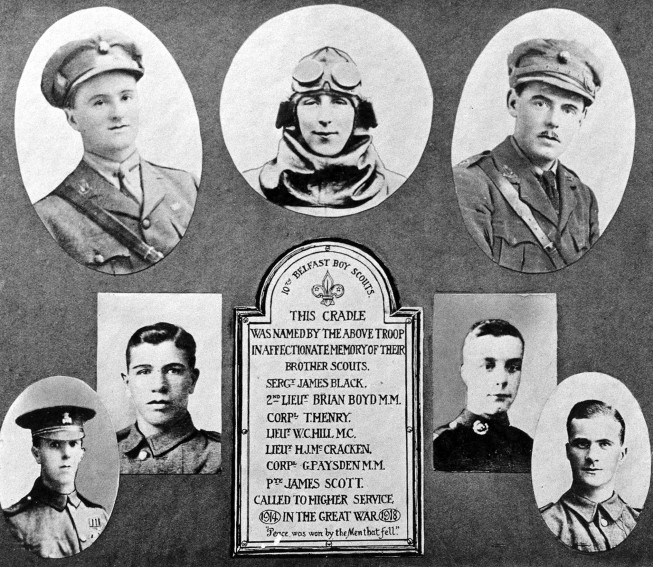

Seven 10th Scouts would die in the war, among them two of the original Owl Patrol, Harry McCracken and Brian Boyd. Harry was related to the Henry Joy McCracken who led the United Irishmen at the Battle of Antrim in 1798 and was hanged in Cornmarket. (Stewart Parker of the Tenth would later write a play about him, entitled Northern Star.) A Royal Flying Corps pilot, he tested new machines after their delivery to France. He received a posting to Egypt where, almost on arrival, he contracted dysentery and quickly succumbed. Brian won the Military Medal on 1 July 1916 – one of four 10th Scouts to be decorated for gallantry that day – for carrying a wounded officer to safety under heavy fire. He became an officer himself, remarkably remaining with the 14th Rifles. On 7 June 1917 he went over the top at Messines, carrying the battalion flag, and was one of the first to fall. On the same day W. C. Hill, who won the Military Cross at the Somme, was giving first aid to a German officer when he was shot dead by a prisoner.

Meanwhile, back in Belfast, the Scouts did what they could in the way of home service. In the innocent days before the Somme they held a cake-baking competition: the entrance fees went to the Belgian relief fund and the cakes went to the 14th Rifles at Randalstown. In 1916 George McFall arranged the collection of ‘some millions’ of glass bottles, sorting them in a workshop on the Newtownards Road loaned by Mr H. J. McCracken. This was part of a Local Association project that raised £1,100 for a Belfast Scouts’ recreation hut in France. An ex-10th Scout, Percy Davis, helped man the hut. Initially sited at Bailleul, it was later relocated to Bethune. It was destroyed in April 1918 during a German bombardment. Finally, in the summer of 1918, the Tenth and six other Troops helped bring in the flax harvest at Tullymurry, near Downpatrick.

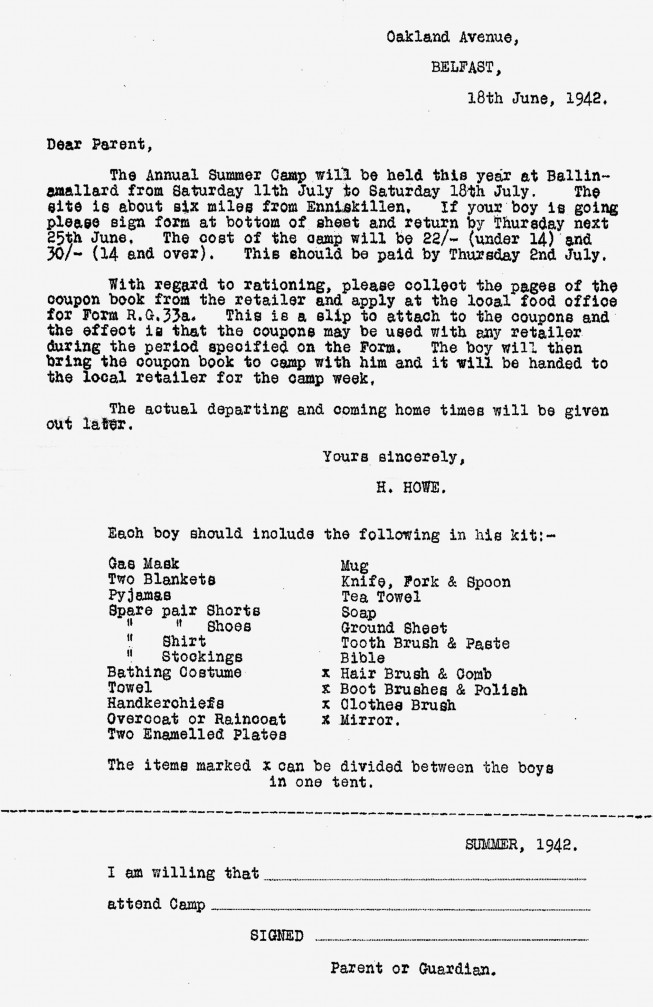

The outbreak of World War 2 in 1939 again saw Scouters head off to join the Forces. Home Guard and Air Raid Precautions units began to operate from the Scout hall, which had its windows painted and covered up for the black-out. Then, in the summer of 1940, the evacuation began of city children to rural areas. Camping was prohibited too. This resulted from a ruling by the Ministry of Public Security, affecting all longer camps that needed to have fires lit for cooking.

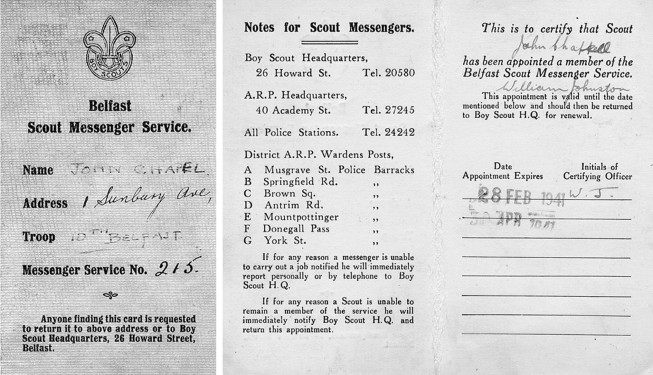

The Tenth’s war service took several forms. Waste paper was collected for recycling and the hall railings went with the paper. Some boys aged fourteen and over joined the Belfast Scout Messenger Service, carrying notes for the civil defence workers, assisting at ARP posts, and helping to fill in emigration forms at the docks. Once, when the Scouts acted as first aid casualties, two of the boys ended up on the roof of the Northern Whig building being told they had to jump and be rescued by the firemen below. Another time the Scouts spent Troop night at Strandtown police station, wearing gas masks and going through de-contamination drills. ‘It was possibly one of the things he did with which we didn’t agree,’ said Larry Walker, but Harry Howe remained ready to volunteer the boys for civil defence preparations.

The Scouts were just back from Easter camp when the first big air raid happened. (The ban on camping had been lifted, provided there were no fires after dark.) Rumours had reached the Scouts on Easter Monday that German reconnaissance planes had been spotted. Then, on Tuesday evening, nearly two hundred bombers filled the sky above Belfast. The Blitz killed over seven hundred people and injured fifteen hundred. Only Liverpool and London lost more people in a single night’s raid. The Scout hall became a shelter for the homeless. The Tenth then met in an outbuilding and field at Norwood Tower on the Circular Road, the home of Sir Christopher Musgrave, Chief Commissioner for Northern Ireland. The Luftwaffe returned in May to concentrate their fire on the industrial heart of Belfast. A bomb fell near Oakland Avenue but failed to explode. The hall could not be used for a week, but meetings continued in the open air. Numbers were falling rapidly now as thousands of children were evacuated from the city. Despite this, and despite the possibility of more air raids, Scoutmaster Harry Howe ensured that the Tenth remained active.

To say how many former 10th Scouts served with the Forces during the war is not possible. After the World War 1 it was a fairly straightforward matter because the Troop was then less than a decade old. By the time of World War 2, however, the Tenth’s ranks of old boys numbered many hundreds. Those who enlisted saw action as far apart as North Africa and Normandy, New Guinea and the North Atlantic. Some had horrific experiences. Robert Clemitson, for example, was with the Royal Artillery in Singapore in 1942 when the island fell to the Japanese. For the next three years he was a worker on the infamous Burma railway, the setting for The Bridge on the River Kwai. Brutal treatment, malaria, beriberi, and cholera were rife. Robert’s Scout training helped him survive the ordeal. Other 10th men did not come through the war. The following are those known to have been killed:

Colin Hugh Buchanan

55 Squadron Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, died on 25 July 1943, age 25. Buried in Sicily.

James Douglas Crabbe

Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, died on 9 November 1942, age 20. Buried in Dundonald Cemetery.

Thomas William Archibald Crone

77 Squadron Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, died on 17 May 1941, age 28. Buried in Belgium.

William Erick Halliday,

Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, died on 10 December 1942, age 25. Buried in Dundonald Cemetery.

John Henderson

Royal Navy, died on H.M.S. Puckeridge on 13 December 1941, age 23. Commemorated in Pembroke Dock Cemetery, Wales.

Thomas Alexander McCord

211 Squadron Royal Air Force, died on 6 January 1941, age 19. Commemorated in El Alamein War Cemetery, Egypt.

David Stanley Peattie

Royal Air Force, died at Perdido, Alabama, USA, on 21 May 1942, age 19.

G. Rippett

Pilot, United States Army Air Forces, died in New Guinea on 14 January 1945.

Robert William Ritchie

Merchant Navy, died on 15 July 1942, age 22. Commemorated on Tower Hill Memorial, London.